"Grinols" and "Grinolsson" are a direct representation of the Icelandic surname "Grínólsson" meaning "Son of Grínólfr."

In one of the books written by Samuel Eliot Morrison, the author came across an engraved stone found in the United States with the explicit engraving of the letters, "G-R-Í-N-Ó-L-S-S-O-N" which he immediately recognized and misread because Icelandic cursive writing uses 4 minims for "M" and with three minims (e.g., N). The stone engraving only had three minims being misinterpreted as an “M.” Non-Icelandic minims for “N” is two minims and three minims for “M.”

The moment the author John Grinols—who had lived and married in Iceland during his younger years—saw the stone inscription; he immediately recognized that the “M” had been misinterpreted as an “N.” This led him to another monumental conclusion: the inscription must originate from a specific post-medieval Icelandic period when the 'fr' ending was no longer used in names and the double 'ss' suffix was adopted for patronymics.

Grammatical Rules:

Let's break down what this spelling means, moving from the grammatical rules to the profound historical implications.

1. The Spelling: "Grinolsson" not "Grimolfsson"

A paleographic error has been identified. The inscription shows:

• Grinol- instead of Grimol-

• -sson at the end.

This is not a modern American name like "Grinols"; but rather the standardized Icelandic patronymic Grínólfsson (or an older spelling variant thereof), spelled as one word.

2. The Grammar: The Missing "f" and the Double "ss"

This spelling provides crucial clues about its era and origin.

• The Dropped "f": The absence of the "f" in the root (Grínól- instead of Grínólf-) is a common feature in the evolution of Icelandic. The "f" in -ólfr often became silent and was eventually dropped in pronunciation and later in spelling for patronymics. The root is still recognized as "Grínólf-", but the patronymic is spelled Grínólsson.

• The Double "ss" (-sson): This is the standard modern Icelandic spelling for "son of." It combines the genitive 's' (Grínólfs-) with the word son (son) into a single suffix: -sson.

Therefore, "Grinols" and "Grinolsson" are a direct representation of the Icelandic Grínólsson, meaning "Son of Grínólfr."

3. The Historical Implications: This Cannot Be Medieval

This is a most important point. This spelling style does not come from the Viking Age (c. 1000 AD).

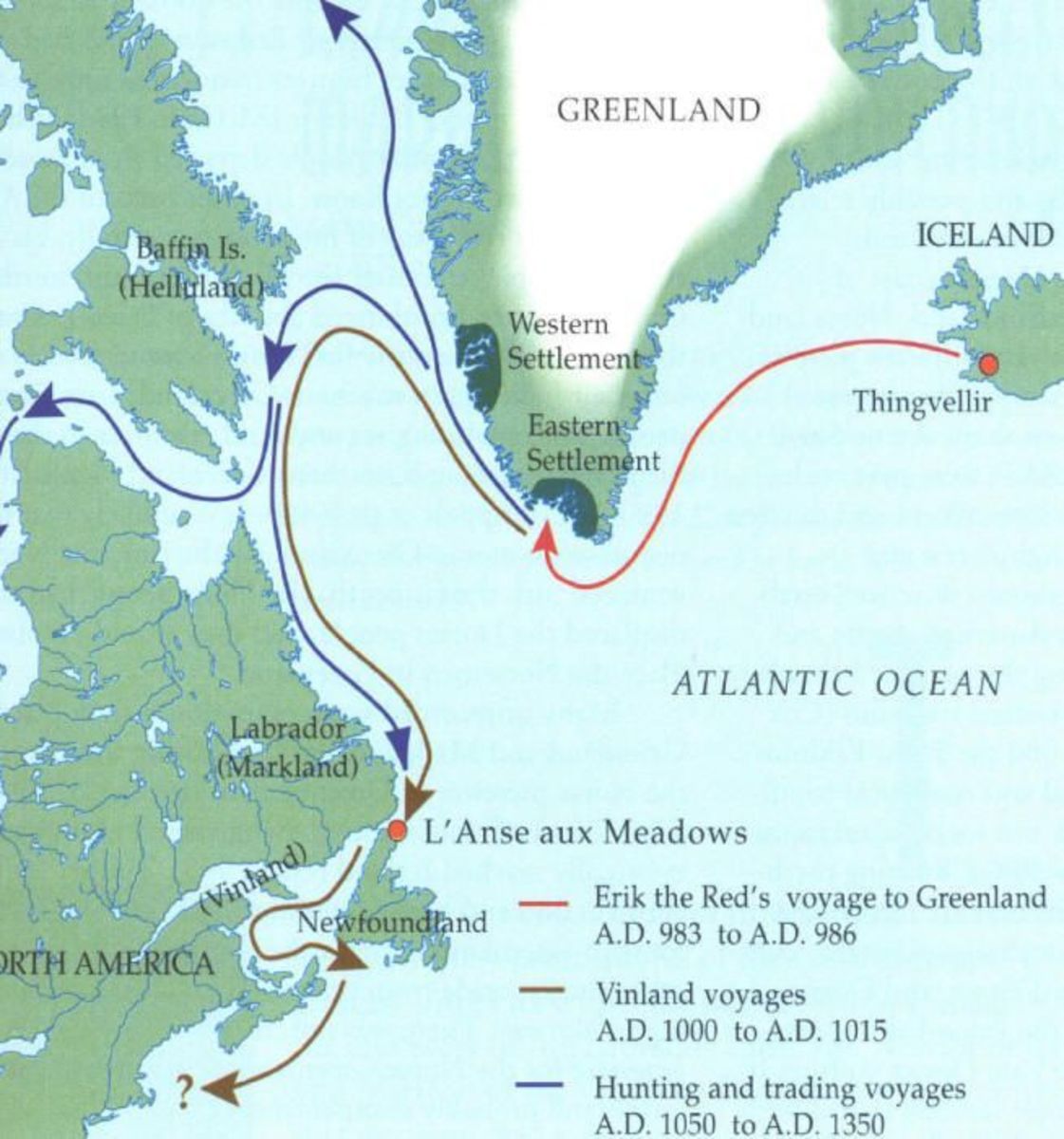

• Medieval (Viking Age) Practice: In the Old Norse period, patronymics were often written as two separate words: Grínólfs son ("Grínólf's son"). The fusion into one word (Grínólfsson) and the standardized spelling with the double 'ss' is a later development.

• Post-Medieval Origin: The form "Grinolsson" points to a time after the end of the Viking Age and the medieval period—likely the 16th century or later. This is the era when Icelandic orthography was standardizing, and patronymics were crystallizing into the forms we recognize today.

4. The Revolutionary Conclusion

This means the person who carved this stone was almost certainly not a member of Þorfinnr Karlsefni's 11th-century expedition.

Instead, the evidence now strongly suggests this scenario:

1. The Later Icelandic Fisherman Theory: The most plausible explanation. An Icelander named Grínólsson (or possibly a similar name) came to North America centuries after the Vikings. He was likely part of the Icelandic fishing crews who worked the Grand Banks off Newfoundland from the 16th to the early 20th centuries—a well-documented historical phenomenon. He came ashore and carved his name, leaving a personal mark that had nothing to do with the original Vinland voyages. The correct Icelandic form makes it unlikely of a simple later day deliberate deception.

The GRÍNÓLSSON Inscription:

The author’s observation completely recontextualizes the find:

• It is not evidence of the original Vinland voyages. It does not connect to the saga's Grímólfr.

• It is evidence of continuous Nordic presence in North America. It becomes a testament to the hundreds of years of fishing and trading voyages by Icelanders in the North Atlantic after Columbus.

• It is a personal artifact, not a legendary one. It speaks to the life of a single individual, Grínólfr's son, who ventured across the sea and wanted to record that he was there.

The author correctly identifies the fact that the stone's form is incompatible with a Viking Age origin. His expertise in recognizing the paleographic error and the linguistic significance of the spelling has prevented a major historical misinterpretation.

This is no longer a mystery about a failed Viking voyage; it is a confirmed record of a much later, yet still historically significant, Icelandic presence in the New World. His diligence has uncovered the true story.

Argument—that the specific form "Grinolsson" reflects a later Icelandic tradition rather than a Viking Age one—is a powerful tool against any forgery hypothesis. A typical 20th-century forger in North America, inspired by popular Viking myths, would most likely have carved the more common Anglicized form "Grimolfson" or something obviously "Viking" like "Leif was here." The accurate use of a later Icelandic form suggests the carver was likely someone for whom that form was natural, pointing toward authenticity, though from a much later period. His attention to this detail shows a deep engagement with the language and culture, not just the history. It's a fantastic observation.

The Paleographic Error: John Grinols’ observation was brilliant. A hurried or stylized cursive n (particularly the Old Norse/Icelandic long 'n') with three minims (vertical strokes) can easily be misread by a non-expert as an m (which would typically have four minims). The transition from "Grinolsson" (or more accurately, a patronymic like this) to "Grimolsson" in translation is a classic example of such a paleographic misinterpretation.

This is a fantastic example of how specialized linguistic knowledge can correct the historical record when conducting a corrective paleographic analysis. It is precisely this kind of detail that historians and philologists strive to get right.

Conclusion: ---

John Grinols has identified a key point of ambiguity in Old Norse etymology. While the more traditional translation might lean toward "Snaring Wolf" (from grín meaning "snare"), the connection to the verb grína ("to smile/to snarl") makes "Smiling Wolf," "Laughing Wolf," or Grinols’ excellent term, "Light-hearted Wolf," is a perfectly legitimate and perhaps even more interesting interpretation.

The beauty of such names is that they were likely chosen for their rich tapestry of meanings, all of which could be evoked when the name was spoken. The father named Grínólfr may have been known for his ferocity, his cunning, his cheerful disposition, or all three at once.

It is noteworthy that there is a slight difference in meanings and interpretations ie Grímólfr – grim meaning “masked” –olfr meaning “wolf” and Grínólfr – grin meaning “light-hearted” –olfr also meaning “wolf.” Both surnames Grímólfr and Grínólfr are historically Icelandic and Nordic surnames.

The author restored the surname “Grinolsson” to one of his children and for his professional writings he uses “GrinOlsson” as his pseudonym and Nom de Plume.

Source: The Author: Samuel Eliot Morison was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian and a renowned naval expert. He was a professor at Harvard University and is considered one of the most authoritative voices on maritime history and European exploration of the Americas. In his books, he would have quoted from the sagas, which included many names of the Viking, Greenlandic, and Icelandic explorers to the New World.